As soon as I entered Art Mumbai, I had an overwhelming realisation of my adoration for art and design. No one, and I repeat, no one other than someone who’s genuinely in love with art would willingly subject themselves to the excursion it takes to reach Mahalaxmi Racecourse. Apparently, taxi drivers don’t care that it carries iconic stature, colonial legacy, and vintage architecture.

It was my first time at an edition, and the first thing I saw didn’t disappoint: a mirror under a plaque that reads “Currently under interpretation.” Beyond the flattering implication that I was a piece of art, I was intrigued by how it asked the audience to keep an open mind and perspective about what awaited them.

I was ready.

The first piece that stopped me in my tracks was Subodh Gupta’s The Seven Colours. Hundreds of stainless steel tongs, coated in PVD, burst from the wall like a firework frozen mid-explosion. The chimtas (a staple in Indian kitchens) were meant to become a commentary on India’s industrial rise, middle-class domesticity, and mass manufacture.

The Seven Colours by Subodh Gupta

Then there was Remen Chopra W. Van Der Vaart’s Meandering Histories Intertwined. I had to lean in close to look at this piece. Carved from recycled wood and set against fragments of woven carpet, its multidisciplinary approach seemed like a map.

Meandering Histories Intertwined by Remen Chopra W. Van Der Vaart

Bharat Sikka’s KOTOKUNIBITO series, with three photographs of Japanese vending machines, initially seemed simple. But reading his perspective helped. The title translates to “the stranger,” which was a nod to his perspective as a traveller navigating unfamiliar terrain. Each machine (yellow, blue, and white) stands in solitude to metaphorize human absence.

Now, I want to come to my two favourites.

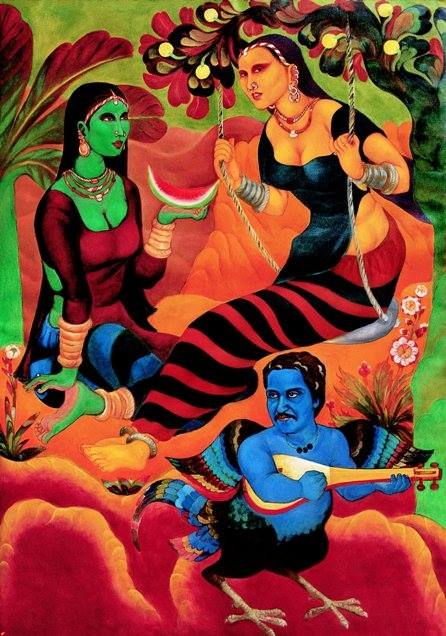

- Ramachandran’s early drawings from 1965-80, all untitled, adorned a wall. Contrary to his signature grand-scale paintings and murals, these were rural sketches. They were intimate and personal, the lines were frenetic – showing how he was working through ideas, improvising as he saw fit. Informed by Romantic and melancholic Santiniketan traditions, these drawings were a precursor to his later, more visual language.

Ramchandaran’s ‘Yayati’

A collector’s edition of A. Ramachandran’s early works

To my pleasant surprise, right after this display, I walked by Raghu Rai’s Trees series. I’ve followed his work for quite some time (after being introduced to him in a photojournalism course). A collection of black-and-white photographs, the legendary photojournalist’s work focused on something quieter – trees as living memories of human existence. The intimate images showed humans in their most vulnerable forms, struggling with the subtle but overarching passage of time.

P.S. A special mention for his daughter Avani Rai, just because I admire her work too.

Raghu Rai’s ‘Trees’

And then there was Kanu Gandhi’s private atlas of one of history’s most public figures: Mahatma Gandhi. Kanu, Mahatma Gandhi’s grand-nephew, interestingly came to be known as “Bapu’s Hanuman” for his devotion.

Over twelve years, armed with a Rolleiflex and a roll of film, he documented Gandhi’s daily life under three strict conditions: no flash, no posed shots, and no requests for funding from the Ashram. You see Gandhi reading, resting, and standing at Juhu beach, surrounded by followers.

It was thrilling to see the result live in a grid of fifteen silver gelatin prints with sepia toning, its earthy browns reminiscing the age it represented.

Kanu Gandhi’s photo-documentary on M.K. Gandhi

I stumbled upon Roger Ballen’s New Colour Works next, and honestly, I didn’t expect to be taken aback. Distorted, mask-like faces, animals positioned like props, old televisions, broken accordions, and wooden trays spread across the portraits. His signature eerie, claustrophobic interiors were still intact, but they were now in muted blues, sticky yellows, and an unsettling grey-green. It was… scary.

And that’s when it struck me that it was European Surrealism, reborn in the South African society. The same illogical, dreamlike quality that defined Dali’s melting clocks or Magritte’s floating apples. This was Ballen’s way of documenting something stranger than just fantasies: reality as psychological theatre.

Also, quick shoutout to Salvador Dali’s The Burning Giraffe.

Roger Ballen’s New Colour Works

Then came Dinabandhu Das’s The Looking Glass (Arshinagar). Nine photographs, arranged in a perfect grid, each one showing an empty room with checkered floors, ornate mirrors, and wooden furniture frozen in decay. The story behind this architectural documentation is interesting: Das had been commissioned in the 1970s to photograph old houses in Calcutta and Bengal for a book on vernacular architecture. But somewhere along the way, he went rogue.

There was no hint of movement, no photographer too; it was like the room was in a vacuum of its own. He’d used in-camera masks and double exposures (borrowed from film special effects) to remove any trace of human presence, even his own.

Dinabandhu Das’s The Looking Glass (Arshinagar)

When I turned the corner, plastered across a vibrant yellow wall were Ketaki Sheth’s Behind the Marquee photographs. Obviously, I had to stop and stare at this portal to old Bollywood. These were the messy, human, behind-the-scenes reality of the glossy pictures we see in tabloids. Sheth had spent years documenting film sets, premieres, and parties, first as a reporter for the Times of India and later for Filmfare.

Ketaki Sheth’s Behind the Marquee

The access was wild: Rekha mid-shoot, Chunky Pandey in his bedroom surrounded by posters of himself, Sunny Deol at home with his dog, and Amitabh Bachchan on three different sets.

Ketaki Sheth’s Behind the Marquee

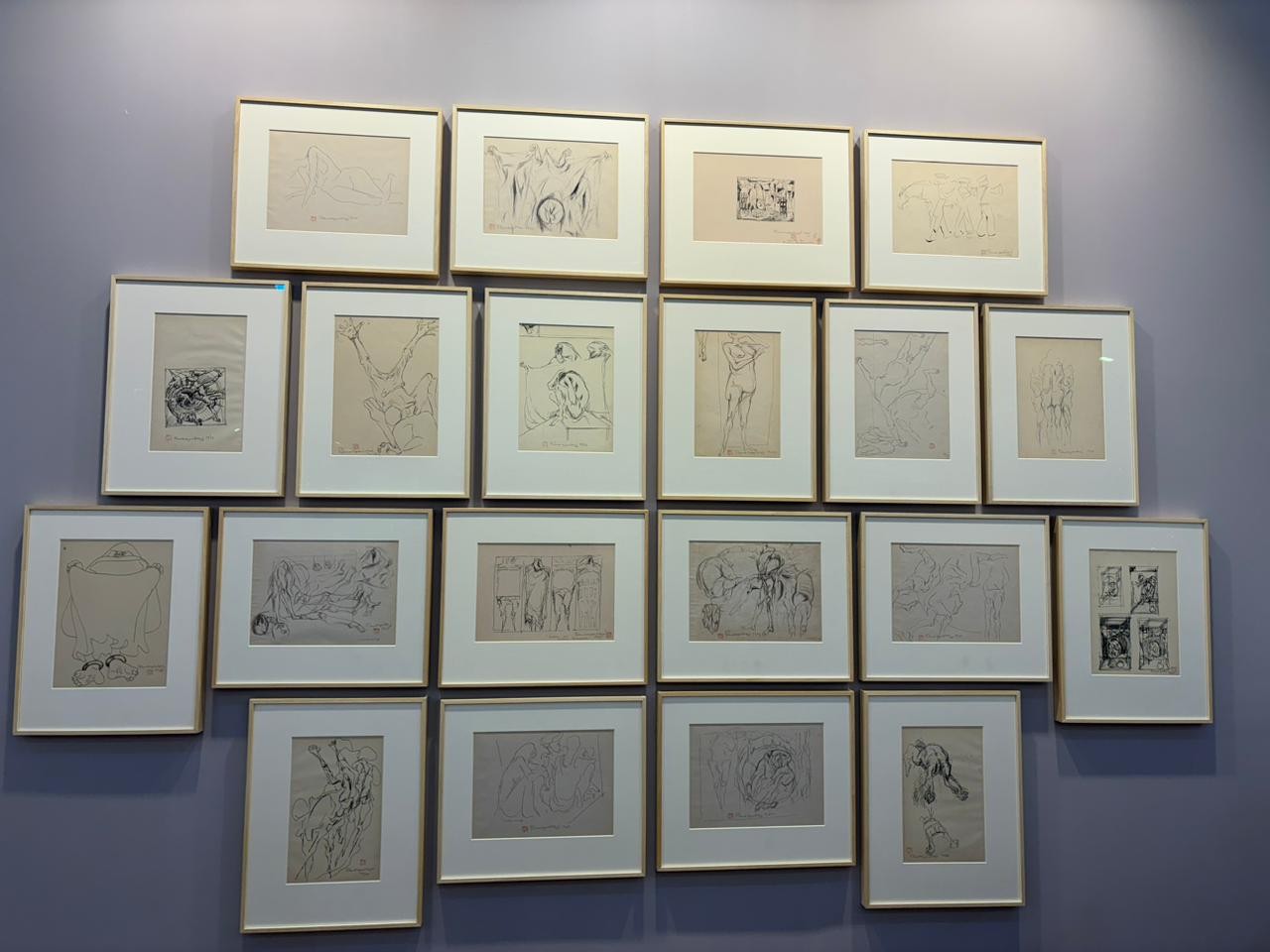

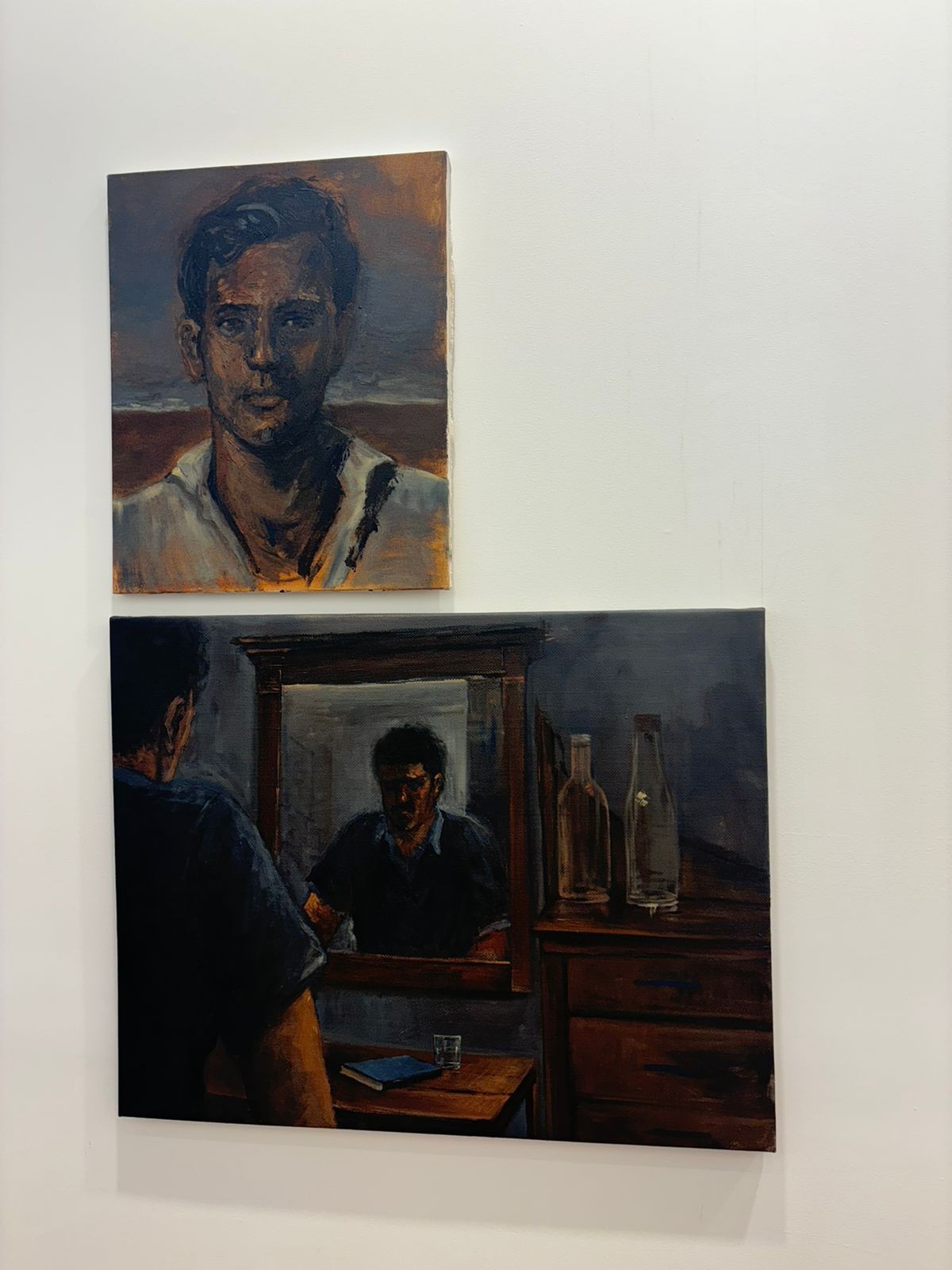

I also noticed Zaam Arif’s The Double. These were two oil paintings hung in an unusual arrangement, one smaller canvas above a larger one, both in muted blues, browns, and shadows. The top piece was a portrait of a man staring at the audience (almost into my soul!) while the one below it had a figure sitting in a dimly lit room, facing a mirror that reflected his own image. The protagonists were “charged with a deep interiority,” grappling with estrangement and disassociation as they questioned the meaning of life in a world with no easy answers. The placard mentioned Albert Camus, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Satyajit Ray.

Zaam Arif’s The Double

By the time I walked out of Art Mumbai, my feet aching and my mind buzzing, I realised something: such fairs are all about the conversations that art incites. I could see perspectives shift as people gazed at an artist’s life’s work and there were moments when the audience physically smiled looking at sculptures. They were seeing the world through someone else’s eyes.

And if this is what Art Mumbai offered in its third edition, I can only imagine what’s coming next for platforms that champion art and design in India.

Of course, I’m not-so-subtly talking about Design POV India that takes a radiacal approach to showcasing architecture and art. It’s set to return in 2026 at the Jio World Convention Centre from May 15-17. Unlike conventional setups, it explores how design is personal, intentional, and a living reflection of its creator, sparking meaningful dialogue and inviting audiences to question, respond, and resonate.

For someone like me, who stood mesmerized in front of Subodh Gupta’s shimmering tongs and Raghu Rai’s quiet trees, the idea of walking through 19 distinct narratives crafted by some of India’s finest design minds seems like the best idea out there.